Lana Del Rey's "Question for the Culture": an exercise in the weaponization of White Feminism

In May 2020, the popular singer-songwriter Lana Del Rey (Elizabeth Grant) wrote a controversial Instagram post entitled“Question for the culture.”In this post, which has since been deleted, Grant criticised a number of black female artists for gaining recognition through their sexuality (Compton, 2020).

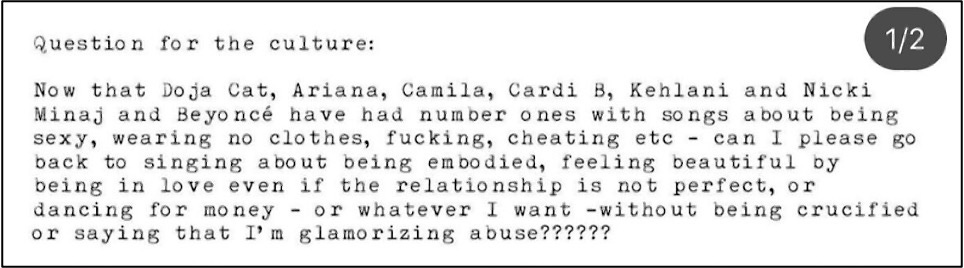

The opening paragraph of “Question for the culture” (Grant, 2020 cited in Compton, 2020)

This left a sour taste in the mouths of many commentators, especially since the post was shared in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement. This triggered a large response from many fans and other women of colour who felt that Grant, a very successful white woman, had no right to victimise herself in the face of black women’s success (Compton, 2020).

Grant responded with a second post:

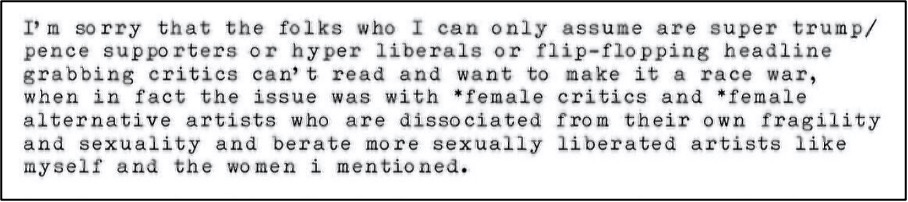

An excerpt from Lana Del Rey’s response post (Grant, 2020 cited in Compton, 2020)

Instead of taking responsibility for the inappropriate criticism of black sexuality in her original post, she sarcastically lashes out at commentators and refocuses her argument around “females”, conveniently omitting race altogether.

Using this example, this blog will explore white women’s role in the social construction of “whiteness” as a mechanism of power, with a specific focus on the weaponization of white feminism to marginalise people of colour.

Race as a Social Construction

To understand Whiteness as a mechanism of power, we must first explore race as a social construction. Race can be understood as a “symbolic category” in the sense that it is a marked difference that is actively created and upheld by human beings. The symbolic category of race categorises people into groups based on their phenotype (physical appearance), ancestry (family lineage), or both (Desmond and Emirbayer, 2009).

This concept of ‘race’ is relatively recent – race as we know it today did not exist until the sixteenth century. Although people were still prejudiced against perceived ‘others’, these ‘others’ were not racialised. Instead, the primary division during the middle-ages was based on the concept of ‘civilised’ vs ‘uncivilised’ people. In fact, the racial categories we use today did not begin to develop until the nineteenth century (Desmond and Emirbayer, 2009). It was through the context of American and English slavery that Blackness became associated with “bondage, inferiority, and social death”, while Whiteness became associated with “freedom, superiority, and life” (Desmond and Emirbayer, 2009:338).

However, these racial categories have persevered through a process of ‘naturalisation’, in which something created by humans is mistaken for something natural. Racial groupings are products of specific historical and geographical contexts, but can become misconstrued as unchangeable, inherent and even biological. When social categories become naturalised, alternative ways of viewing the world can begin to seem impossible, despite racial groups’ tendency to shift and transform depending on cultural political and social contexts (Desmond and Emirbayer, 2009).

It is therefore incredibly important to remember that race has been constructed within the context of racial domination, which can be understood through two different manifestations: institutional and interpersonal.Institutional racism can be described as the systemic domination of people of colour manifesting in institutions such as universities, legal systems, political bodies and other social collectives. On the other hand, interpersonal racism can be described as racist interactions between people, whether conscious or unconscious (Desmond and Emirbayer, 2009)

White Feminism as a Tool of White Supremacy

White people, as a social group, hold the power to classify one group of people as ‘normal’ and one group as ‘other’ (Desmond and Emirbayer, 2009). This has meant that Whiteness has often been unexamined in terms of race, as it is seen as the ‘standard’ or ‘norm.’ This is problematic since Whiteness is position of structural advantage and race privilege that has historically oppressed racialised ‘others’ to an extreme degree, meaning that it is arguably more useful to interrogate it as a socially constructed group (Frankenberg, 1993).

This perception of Whiteness as the norm can become particularly harmful when it becomes embedded in social movements. For example, social theorists Dreama G. Moon and Michelle A. Holling argue that, in centring itself solely around the issue of gender, mainstream (white) feminism often hides its participation in upholding white supremacy (Moon and Holling, 2020).

“As white women ignore their built-in privilege of whiteness and define woman [sic] in terms of their own experience alone, then women of Color [sic] become ‘other,’ the outsider whose experience and tradition is too ‘alien’ to comprehend.”

(Lorde, 1984 cited in Moon and Holling 2020)

As Audre Lorde suggests in this quote, the centring of white women within the feminist movement ultimately leads to the marginalisation of women of colour (Lorde, 1984 cited in Moon and Holling, 2020). When white feminism addresses “women” as a collective group, it tends to ignore the structural inequalities between the women making up this symbolic category.

When this is challenged by people of colour, the narrative of “white victimhood” often begins to play out. Moon and Holling suggest that white identity relies on a “discourse of white victimisation” (Moon and Holling, 2020:225) as a mechanism of white supremacy. Therefore, it is unsurprising that this narrative has found its place within white feminism, where women portray themselves of victims of white patriarchy without acknowledging their privilege as racial oppressors (Moon and Holling, 2020).

This is aptly demonstrated by Lana Del Rey’s Instagram posts. Firstly, she indirectly claims that she is being racially marginalised by positing herself against successful women of colour. When she was called out for the racist undertones in this statement, she responded with exaggerated claims of attack. This has often been termed “white fragility” by scholars of race (Moon and Holling, 2020). She then demonstrates her viewpoint that Whiteness is the norm by evoking the term “female”, refusing to acknowledge her privilege as a white woman.